The concept of the ‘language market’, proposed by Bourdieu (1998), is relevant to understanding the field of power relations imbricated in the constitution of the English language as a valuable linguistic capital and its configuration as a commodity in the globalized economic market.

Bourdieu’s studies of the field of social sciences to power relations, hierarchization, and linguistic monopolization considered that “linguistic exchange is also an economic exchange established amid a certain symbolic power relationship between a producer, equipped with linguistic capital, and a consumer (or a market), capable of providing a certain material or symbolic profit” (Bourdieu, 1998, p. 53).

Based on this assumption, Bourdieu (1998, p. 54) analogously examined that the exchange relationship that occurs in the economic market also appears in a language market,

Characterized by a particular law of price formation: the value of the discourse depends on the relationship of forces that is concretely established between the linguistic skills of the speakers, understood at the same time as their capacity for production, appropriation, and appreciation or, in other words, as the capacity of the different agents involved in the exchange to impose the most favorable criteria of preference on their products.

(Bourdieu, 1998, p. 54)

Cox (2008, p. 30), when analyzing the “value of speaking from Cuiabá in the linguistic market of Mato Grosso”, argues that the consequences of this analogy show that “the situation is not confined to the immediate context of interaction, but encompasses global structures”. According to the author, “the linguistic and symbolic markets show a certain degree of unification that mimics the unification of the economy and the circulation of cultural goods”.

Bourdieu (1998, p. 37) explains that the “politics of unification” and the dimension of the “market for symbolic goods accompanies the unification of the economy”. It means that the process of unifying the market for cultural goods corresponds to the economic circulation of these goods in an exchange relationship that favors those with a more excellent supply of linguistic or symbolic capital.

Under these precepts of the language market, Park and Wee (2012) problematize how and why English is seen as constituting valuable linguistic capital in contemporary globalized society. Similarly, Jordão (2011, p. 224) enquires,

How a language’s symbolic and cultural power lies not in its internal characteristics, or in its structures, lexicon or grammar, but in its social functioning, in how this language is positioned culturally”. In other words, […] how a language becomes powerful through the use that powerful people make of it.

(Jordão, 2011, p. 224)

In addition, the linguists Tan and Rudby (2008), Tupas (2008), and Heller (2010) focus on the proposition that the recent phenomenon of the commodification of languages is one of the effects of the cultural policies of the new global economy, point to the fact that the global/local interests that are currently being undertaken by languages represent an investment in them as a cultural capital that can be exchanged in a worldwide language market. Investment in them as cultural capital that can be exchanged on a global language market.

With the contribution of these pre-established concepts by Bourdieu (1998), the Canadian sociolinguist Heller (2003, 2005, 2010), Tupas (2008), Tan and Rudby (2008), Cameron (2002, 2013), Block (2008, 2014), Pennyccok (2008), among others, draw attention to the process of specific languages – economically powerful languages – acquiring monetary value in the current globalized economic market and rearticulating their historical roles as cultural repositories and identity brands.

In this sense, Heller (2010) argues that when we consider language as a commodity, we think of a specific and emerging form in the characteristics of its exchange values, especially when it is exchanged for material goods or money.

Likewise, Pennycook (2008) says that when we see languages as commodities per se, we consider them under their instrumental, pragmatic, and commercial aspects, reflecting dominant discourses of language choice and teaching and learning policies.

References:

BOURDIEU, P. A economia das trocas linguísticas. 2. ed. São Paulo: EDUSP, 1998.

BOURDIEU, P. O poder simbólico. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2000.

COX, M. I. P. Quanto vale o falar cuiabano no mercado linguístico mato-grossense. São Paulo: Vozes, 2008.

HELLER, M. Language, skill and authenticity in the globalized new economy. Noves SL. Revista de Sociolinguística, Winter, 2005. Disponível em: <http://www.gencat.cat/llengua/noves/noves/hm05hivern/docs/heller.pdf>. Acesso em: 20 abr. 2013.

HELLER, M. The commodification of language. Annual Review Anthropology, v. 39, p. 101-114, 2010.

JORDÃO, C. M. A posição do inglês como língua internacional e suas implicações para a sala de aula. In: GIMENEZ, T.; CALVO, L. C. S.; EL KADRI, M. S. (Org.). Inglês como língua franca: ensino-aprendizagem e formação de professores. Campinas, SP: Pontes, 2011. p. 221-252.

PENNYCOOK, A. Preface. In: TAN, P. K.W.; RUDBY, R. Language as commodity: global structures, local marketplaces. London: Continuum, 2008.

Images:

It is available at https://www.geekie.com.br/qual-o-papel-da-lingua-espanhola-plano-de-aula/. Access on Nov 15 2023.

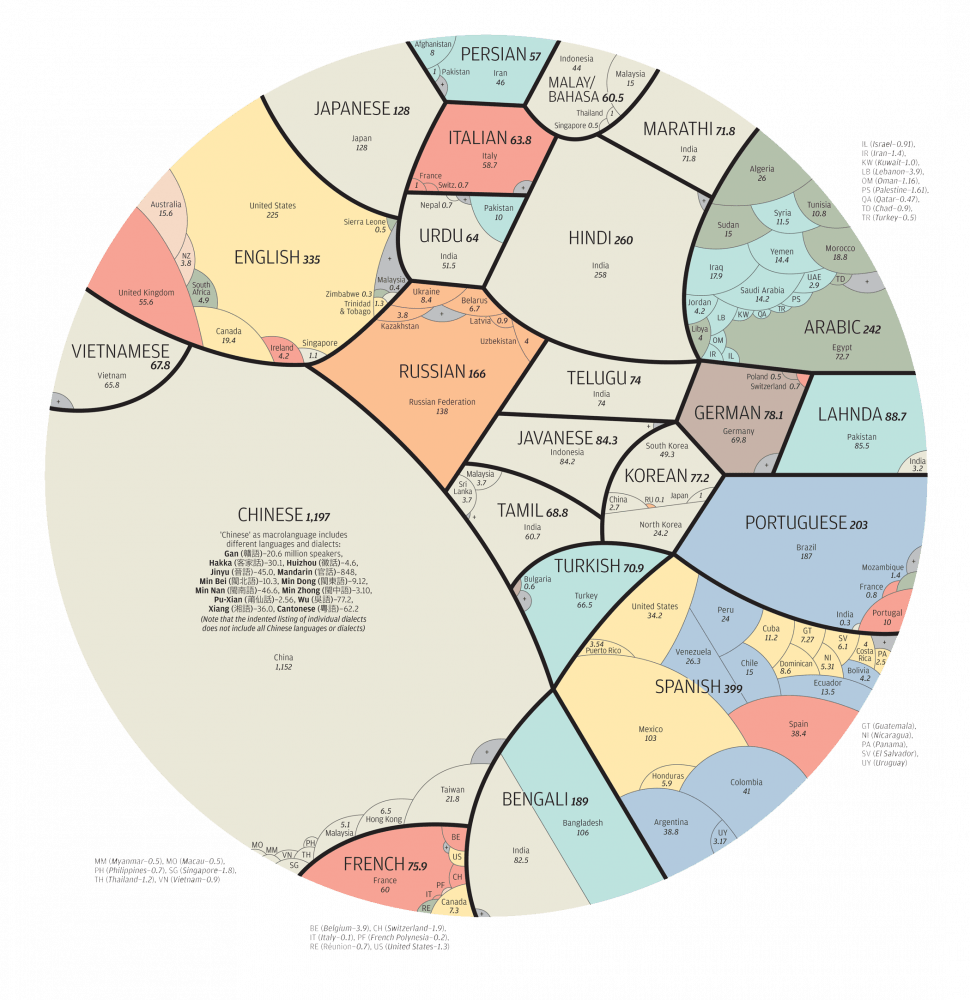

It is available at https://www.hypeness.com.br/2021/12/infografico-das-linguas-do-mundo-as-7-102-linguas-e-suas-proporcoes-de-uso/. Access on Nov 15 2023.