A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON LANGUAGE LEARNING FROM ‘LEAGUE OF LEGENDS’ DURING THE (POST)PANDEMIC TIMES

Sávio Sayuki Satake

Supervisor: Raquel Silvano Almeida (Universidade Estadual do Paraná)*

ABSTRACT

This research paper aimed to analyze how the video game League of Legends (2009) can be an effective virtual tool for English language learning. Data were collected during the pandemic and post-pandemic times, derived from the Covid-19 virus, in 2021 and 2022. To reach the goal, we outlined three objectives: 1. Analyze English vocabulary learning in two groups of League of Legends (2009) players; 2. Examine if the vocabulary used in the game League of Legends(2009)affects the players’ real-life situations, and 3. Check if playing video games is a motivating activity for the players to learn a foreign language such as English. We adopted qualitative-quantitative research, as we designed and applied two semi-structured questionnaires to the video game players. We had 40 respondents during the pandemic and 15 during the post-pandemic. In the theoretical foregrounding, we provided a short literature review on game-based (language) learning (GEE, 2009; SHAHRIARPOUR, N. et al., 2014; OSMA-RUIZ, 2015; MORAN, 2015; BNCC, 2018; ALMEIDA, 2022). Data systematization consisted of nine aspects: gender, age, video game consumption, language, new vocabulary, intuitive learning, motivation for learning English through video games, English vocabulary learned in the game, and use of the learned vocabulary in a real-life situation. Finally, we concluded that playing video games is not only a moment of pleasure or a hobby. Several people are taking it and developing other skills with or through it. As teachers, we need to take this and use it as an advantage in our English classes, not seeing it as an enemy but as a pedagogical tool to make students aware that English is relevant to their lives.

Keywords: Video games. English language learning. (Post)pandemic.

Introduction

League of Legends (2009) is one of the most popular games played online. According to Salles (2021), it is the 9th best-played game online. There are around 115 million players per month and almost 8 million daily, causing a worldwide impact in the market of video games.

The company creator of League of Legends (2009), Riot Games, has expanded through popular culture, developing music with the band Pentakill, the virtual group KDA, with over 400 million views on YouTube, also creating products of the games. They are also the creators of another popular FPS (first-person shooter) online game called Valorant (2020) and most recently they made a Netflix series named “Arcane”, one of the most well-rated series of all time. It became, as Jenkins (2006) points out, a franchise “forcing the mediatic industry to accept the convergence” (JENKINS, 2006, p. 45).

During the worldly pandemic time – 2020 and 2021 – caused by the Covid-19 virus, the community of video game players expanded since we had to stay home. Thus, this research interviewed online gamers at the end of the pandemic 2021 and the beginning of post-pandemic 2022.

As I mentioned before, the game League of Legends (2009) is played by thousands of people every day. Just like other games, we have some terminologies that are used inside the game and in the community of players, and those terminologies are just in English. So with that being said, How was the video game ‘League of Legends’ (2009) an effective virtual tool for the learning of English language vocabulary during the (post)pandemic? To investigate that in this paper, I established the following aims:

General objective:

Study how the video game League of Legends (2009) was an effective virtual tool for the learning of English language vocabulary during the (post)pandemic.

Specific objectives:

- Analyze English vocabulary learning in two groups of League of Legends (2009) players.

- Examine if the vocabulary used in the game League of Legends(2009)affects the players’ real-life situations.

- Check if playing video games is a motivating activity for the players to learn a foreign language such as English.

Theoretical framework

In the theoretical framework, I provide a short literature review on game-based (language) learning and the game League of Legends (2009) to support this research’s data with a sound theory.

Game-based (language) learning in education

Blended learning is quite relevant to education in the present day, “[…] It is a wider and more creative ecosystem. We can teach and learn in countless ways, in every moment, in multiple spaces.” (MORAN, 2015 p.1). Blended learning goes beyond traditional teaching, incorporating several methodologies by bringing the learner’s background into the teaching and learning processes.

Brazilian-Spanish researcher José Moran (2015) states that formal education is increasingly blended, mixed, and hybrid because it takes place not only in the physical space of the classroom but in the multiple spaces of everyday life, such as digital ones. Teachers may communicate with their students face-to-face and virtually by using mobile technologies and balancing the interaction with one and the other.

Moran (2015) also points out that in blended learning some components are essential to successful active learning, such as: creating challenges, activities, and games. They bring in the skills needed for each stage, ask for pertinent information and offer rewards that combine every personal background with meaningful participation in group works. That is all carried out with adaptive platforms which recognize each learner while learning by interacting, and all using appropriate technologies.

Furthermore, according to Moran (2015), games and lessons scripted with the language of games are increasingly present in everyday school life. For generations used to playing games, the language of challenges, rewards, competition, and cooperation is attractive and easy to understand. The collaborative and individual games, of competition and collaboration, of strategy, with well-defined stages and skills, are becoming more and more present in the various areas of knowledge and levels of education.

As for Gee (2009), when players emerge video games, they are going to learn inside the game, but it can be related to their lives:

Recent research suggests that people only know what the words mean and learn new words when they can relate them to the types of experiences they refer – in other words, the types of actions, images, or dialogs to which that word relates. (BARSALOU, 1999; GLENBERG, 1997 apud GEE, 2009 p. 6).[1] (Translated by the author)

From the perspective of video games’ words and their relation with players’ lives, this paper examined how video games can be effective tools for English learning since I assume that players feel comfortable when the video game vocabulary is meaningful. Moran (2015) argues that:

Learning is more significant when we motivate students intimately; when they find the sense in the tasks that we assign; when we consult their deep motivations, and when they engage in creative and socially relevant projects. (MORAN, 2015 p. 5) (Translated by the author) [1]

According to the newly established Brazilian Education Curriculum Guideline – Base Nacional Comum Curricular – BNCC (2018), today, language learning has to be strictly engaged in technologies, culture, and digital media. School pupils need to acquire competence in an additional language – English – in an intrinsic manner with a globalized digital culture, as can be seen in BNCC’s competencies numbers 2 and 5 below:

2. Communicate in the English language, through the varied use of languages in printed or digital media, recognizing it as a tool for access to knowledge, for the expansion of perspectives and possibilities for understanding the values and interests of other cultures and for exercising social leadership.[1] (BRASIL, p. 246) (Translated by the author)

5. Use new technologies, with new languages and modes of interaction, to research, select, share, position and produce meaning in literacy practices in the English language, in an ethical, critical and responsible way.[1] (BRASIL, p. 246) (Translated by the author)

In the BNCC curriculum document, digital culture and English learning engagement also aim to make school pupils motivated to learn and get conscious of language multiliteracy within digital culture:

Young people have increasingly engaged as protagonists of digital culture, getting involved in new forms of multimedia and multimodal interaction, and social network action which are carried out in an increasingly agile way. (BRASIL, 2018, p. 61)[1] (Translated by the author)

In the study entitled Learning English is fun! Increasing motivation through video games by Osma-Ruiz et. al (2015) it was researched how video games can help the acquisition of a foreign language. The authors argue that,

Several authors agree that video games can improve the quality of education. The most recent generations of children, born in the last 20 or 30 years, have grown up in a computerized setting, where the Internet, electronic devices, video games, and all kinds of IT tools have become an integral part of their lives. (OSMAR-RUIZ et al, 2015, p. 1). (Translated by the author)

Recently, numerous studies have shown that video games can not only foster the acquisition of a language but also upgrade the environment. Shahriarpour et. al (2014) show how games can influence students in class and how teachers can use them: “word games can reflect the learners themselves in their classroom and teachers can assess teaching process by themselves through word games as well. These motivate them to achieve a goal” (SHAHRIARPOUR et. al, 2014, p. 1740).

Game-based learning is a new education method incorporating games into the process. In this regard, games or gamification can be divided into two aspects: mechanic and dynamic processes.The mechanic process is “defined as the processes, fundamental actions, and control mechanisms that are integrated into ‘gamify’ activity and to create engaging experiences for learners.” (DEHGANZADEH, 2020, p. 55) The dynamic process “stimulates and triggers the emotions of the learners to experience the game” (DEHGANZADEH, 2020). Making the process of learning something through video games way more interesting and captivating because it makes the player interact with it.

Furthermore, Brazilian science computing professor Marcos Silvano Almeida (UTFPR) (2022), states that there are different profiles of gamers, from the ones who play only for hobby and for fun to the ones that make a living out of playing video games, as it is shown below, in image 1:

League of Legends

In this paper, the game of focus is League of Legends (2009). It is one of the most popular games played online. According to Salles (2021), this game is the 9th most played online, having about 115 million players per month and almost 8 million daily, causing a worldwide impact in the field of video games.

League of Legends has its own unique terminology that is used among all the communities of gamers. The company that created the game, Riot Games, has expanded through popular culture, developing music with the band Pentakill and the virtual group KDA, which has over 400 million views on YouTube, and also creating products for the games.

They are also the creators of another popular FPS (first-person shooter) online game called Valorant (2020), and most recently they made a Netflix series named “Arcane,” one of the most well-rated series of all time. As Jenkins (2006) points out, a franchise is “forcing the mediatic industry to accept the convergence.” (JENKINS, 2006, p. 45).

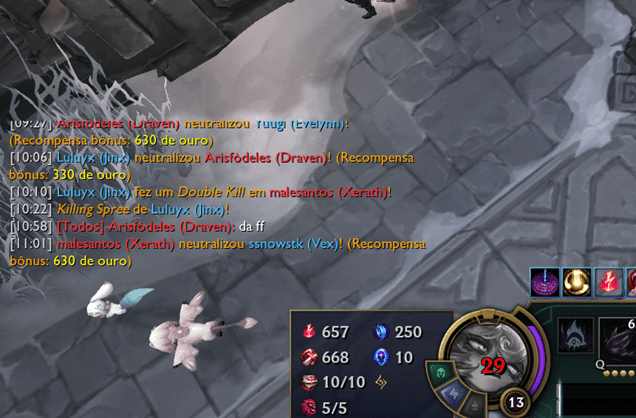

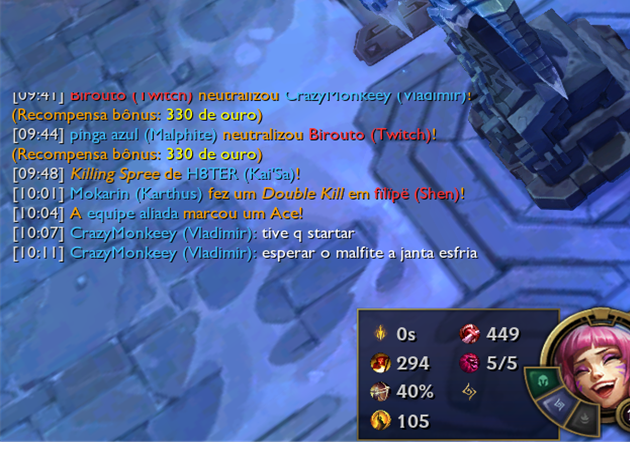

League of Legends was specifically chosen because it is the game that I play the most, and because the community inside the game uses a lot of English terminologies during the matches, they use a lot of those terminologies, as it is shown in Images 2, 3, 4, and 5 below:

Methodology

This research has a qualitative nature, meaning that the data collected in it was analyzed through conversational communication. I adopted a qualitative-quantitative research paradigm, as I understood that the data obtained from the two semi-structured questionnaires, consisting of open and closed questions, applied to League of Legends players during and after the pandemic were objects of social reality and significant information about what was researched. Bogdan and Biklen (1991) contemplate five main characteristics of qualitative research in education:

– the data are collected by the researcher and his/her instruments in their “natural environment”

– the data are described and recorded in the form of words, which allows for richer exploration during the analysis process;

– the researcher’s elements are the research process and care;

– the data are analyzed inductively;

– the importance lies in the meaning of the data provided by those investigated.

In an effort to fulfill my research objectives, I organized two online questionnaires (made available through the game’s chat) directed at players of League of Legends (2009) during the pandemic and post-pandemic as follows:

| Pandemic | Post-Pandemic |

| Date: 04/11/2021 ~ 17/12/2021 Time length: 1 month and 13 days | Date: 01/05/2022 ~ 25/05/2022 Time length: 1 month and 13 days |

The game’s chat is available after every match. There are two teams, yours and the enemy’s, each with five players. When the match is over, all players are directed to a lobby where they can communicate with each other. At this point, I sent them the link to my questionnaire as we can see in image 6 below:

At last, the data collected illustrates the participants in terms of genders, ages, time devoted to playing video games, and how this practice impacted somehow on their lives’ situations in which the English language is present. Furthermore, the responses gathered their thoughts on how video games influenced their English language learning.

Data analysis

In this section, I present the data gathered from the online questionnaires (made on Google Forms) that were sent to League of Legends players when they played the World 2022: LOUD x FNATICS[1].

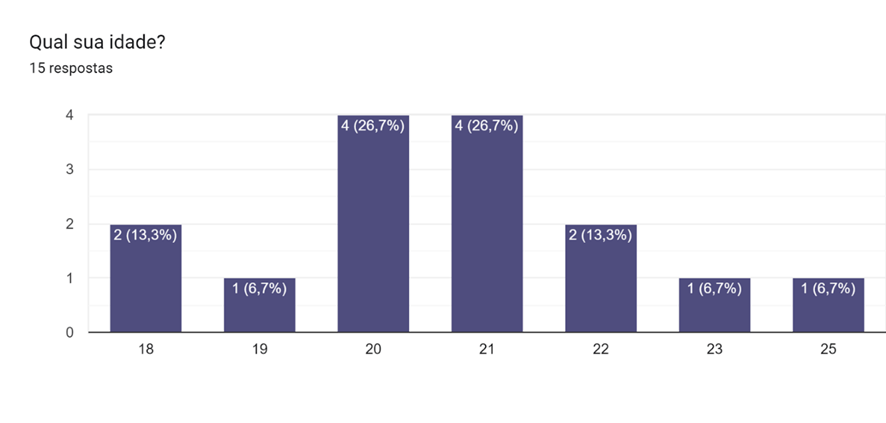

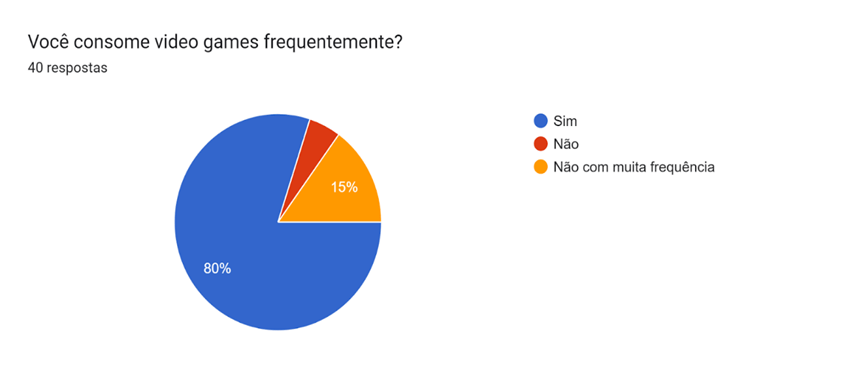

The first graphics show data that was collected during the pandemic, and the second graphics show the data that was gathered in the post-pandemic scenario. The data for both of them was collected within one month and 13 days.

Before analyzing in depth the answers to the questions, it is clear that people tended to play more during the pandemic times since there were 40 respondents. On the other hand, there were only 15 respondents during the post pandemic one, so it is more likely to assume that the community of League of Legends was reduced since the activities were returning to normal and they were not able to play it.

In order to systematize the data analysis through graphics and tables, I categorized them into nine aspects as follows:

- Gender

- Age

- Video game consumption

- Language

- New vocabulary

- Intuitive learning

- Motivation for learning English through video games

- English vocabulary learned in the game

- Use of the learned vocabulary in a real-life situation

By analyzing those graphics, it is noticeable that in both scenarios there was a predominance of female players; more than half of the survey respondents during pandemic times and after the pandemic were female players, at 55% and 60%, respectively.

According to graphics 3 and 4 above, the average of age is an interesting one, because we can see that during the pandemic times, it had more underage players (within 16 years old to 34 years old), and in the post-pandemic data, it had more age of majority (18 years old to 25 years old). We can therefore assume that during the pandemic times, more teenagers could have more access to the game to play it, interacting more than during the post-pandemic times.

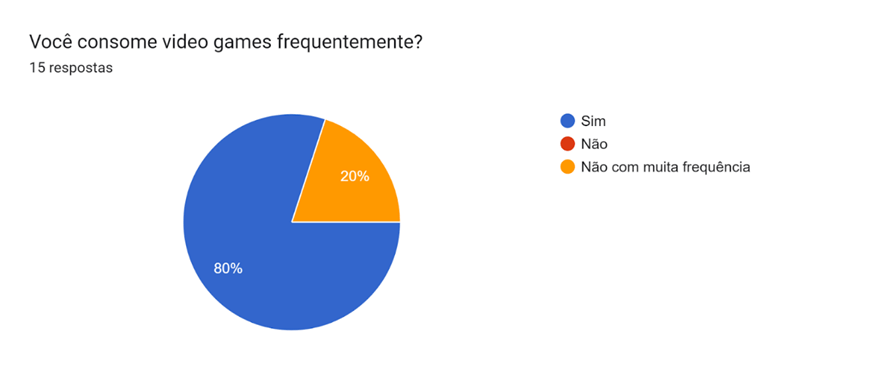

Interestingly, graphics 5 and 6 above show that the majority of both respondents assumed that they frequently played video games (80%).

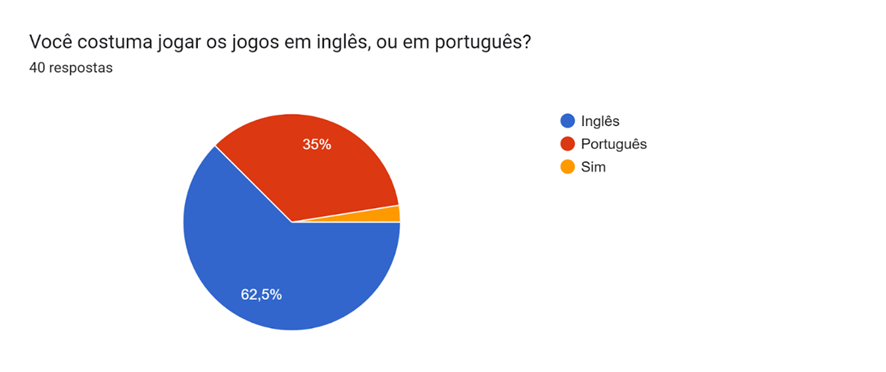

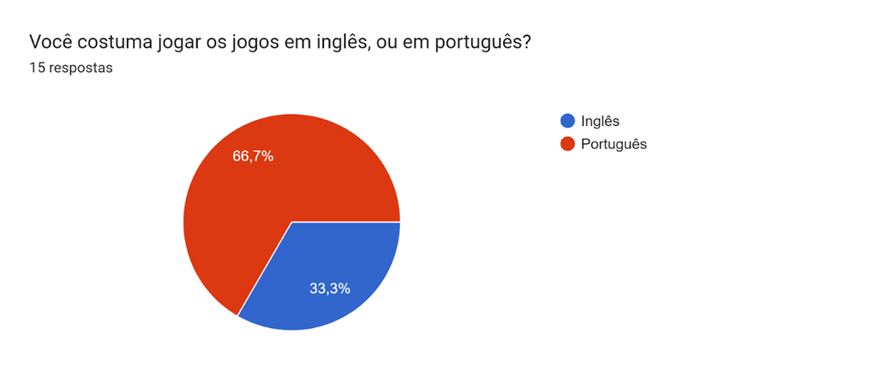

As for graphics 7 and 8 above, the use of English predominated in League of Legends among pandemic respondents (62.5%); however, post-pandemic players tend to play more in Portuguese than in English (66.7%).

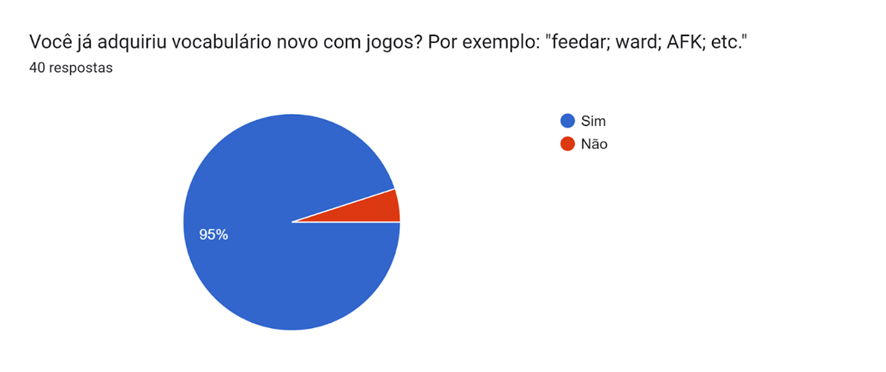

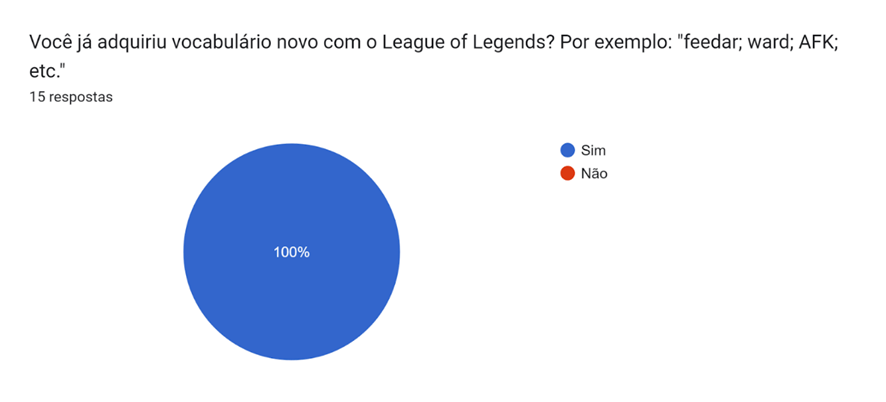

Noticeably, the majority of respondents from both scenarios — pandemic and post-pandemic — affirm that they have acquired new vocabulary through League of Legends (95%) and (100%) as both graphics show above; even though more than half of the post-pandemic players played in Portuguese, they were still able to acquire knowledge of the English language.

In the pandemic time, the respondents said that they learned the following vocabulary:

- feedar, call, floodar, nerfar

- Engage, Tank, Shield etc.

- Meele, ranger, afk, agrar, ks, gankar, summoner entre outras…

- Fatality, finish him, ready, go, nice, perfect…

- Quiver, bow, fatigue, cooldown, respaw, parry, dexterity, strength, inventory, etc

- Character, level, power up, shield,

- Try hard, worth, spree, “death is like the wind, always by my side”, “Kill steal” ou “kill secured”

- Level, attack, score

- Palavras utilizadas em fps em geral: CT, TR, eco

- Easy, Multiplayer,single,language,demo,player e etc.

- win, loss, up, down, mid, são bastantes mas não consigo lembrar kkk

- Jinx, ward, ban, sprouts, hazelnut, harvest, lucky, artisan, attempting….(não lembro mais)

- Comandos básicos de ações, ou instruções do personagem “run, jump, punch, save, exit…” e também frases

- skill, poison, feed, rush, slow, snare, standart, etc

- Noob, quit, rage, rox, afk, brb

- nerd, buff, feed, parry, team figth, bomb site, counter entre outros

- afk

Moreover, in the post-pandemic, the respondents said that they learned new vocabulary by playing the game as follows:

- Shield bow , cleanse , heal , ignite…

- feed, kill spree, dive

- Não especificamente em inglês, mas uso muito “tankar”

- Where are you from? How old are you? Hi! I’m fine, and you?

- Bush, Ward, leash, recall, cooldown

- Farm, Bait, Cait

- bush – arbusto/ wardar – vigiar

- wave, backdoor, snare, poke, stun e não lembro o resto

- Ward, summoner, spell

- Ward, feedar

- league of legends, wakd, lane,

- ward

- givar, feed entre outros kkkk

- ward, fist blood, pentakill, lane, jungle, mid, bot, top

- Ward

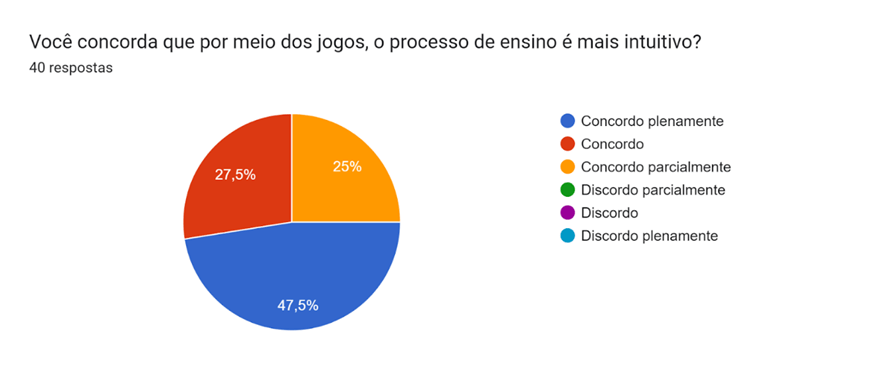

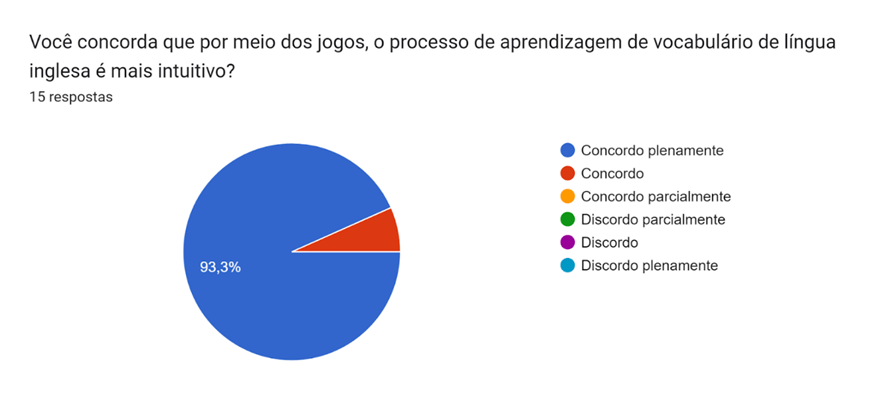

As graphics show above, in the pandemic data all of the participants agreed that video games are a more intuitive way of learning English; the difference between the pandemic and post-pandemic is about how strongly they agreed on that.

The post-pandemic players had a stronger conviction that it can be more intuitive than the pandemic ones, though they all agreed. And they justified why they think that can be more intuitive as follows:

- ”Por ser um meio mais divertido de ser aprendido”

- ”apesar de serem palavras básicas, isso já ajuda a enriquecer seu vocabulário”

- ”se torna mais intuitivo, pois caso você não saiba o básico, você consegue acompanhar o que está acontecendo e assim compreendendo o que está ocorrendo, fazendo sentido na palavra ou frase em inglês.”

- ”Antigamente muitos jogos que eram lançados não tinham dublagem ou tradução, e muitas pessoas que começaram a jogar desde cedo tiveram que ir atrás de aprender o inglês para conseguir completar o jogo. A maioria desses jogos tem histórias grandes, então é um meio de aprendizagem. Porém depende muito da pessoa, e da vontade dela.”

- ”O incentivo ao aprendizado deve ser feito com uma atração prazerosa pra pessoa, decorar termos não gera interação com o idioma, envolver os exercícios com entretenimento é muito mais atraente pro aluno”

- ”Consumir jogos em inglês, faz com que o indivíduo veja diversas palavras comuns e até novas e nisso vai aumentando seu vocabulário e é uma forma legal de aprender algo enquanto joga”

- ”Pelo incrível que pareça, não só jogando mas também, assistindo aos campeonatos de E-sports conseguimos ter um “sexto sentido” na hora de agir ao falar em outra língua.”

- ”Deixa mais divertido por conta da interação”

- ”O que cativa alguém a aprender é a forma que se transmite a informação, a didática, um ótimo exemplo é o Duolingo”

- ”Você está conhecendo novas palavras e se “divertindo” ao mesmo tempo”

- ”Existem muitos jogos que são somente na língua inglesa, e para que você jogue e entenda a história você tem que saber o “básico” de inglês, e aprender outra língua jogando acaba sendo um momento lúdico e ao mesmo tempo um aprendizado.”

- ”Existem alguns jogos que você se obriga a conhecer e aprender inglês… Eu jogava muito um jogo de cozinhar, em um site, e era todo em inglês… Aprendi muita coisa por alí”

- ”Acho que é uma forma mais leve e interessante de aprender”

- ”sem ser só com o “lol”, aprendi a maior parte do meu inglês, antes de ingressar em um curso, com jogos de história e rpg que na epoca nao tinha legendando e nem dublado”

- ”Assim como músicas, filmes e livros, os jogos podem ajudar no seu vocabulário em outras línguas.”

Most of them justify that they think it is more intuitive since it is fun to interact with the video game, so they are exposed to the games in a completely different world, where if they want to enjoy the most, they must be able to interact with the game and also the other players, so in that way, the process of learning is lighter and it can have more interaction with the learner.

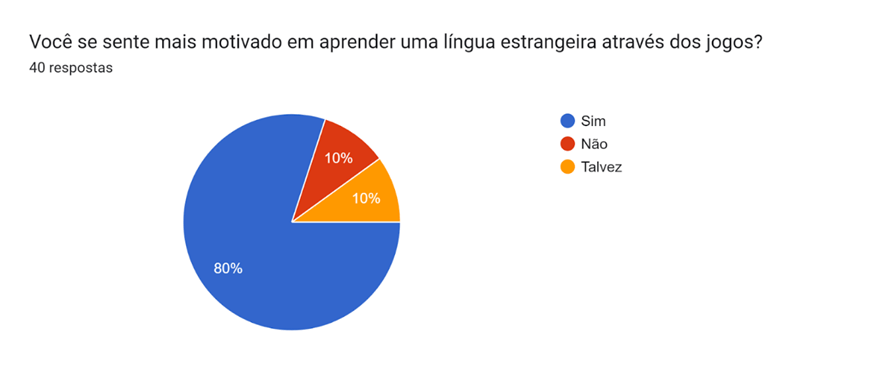

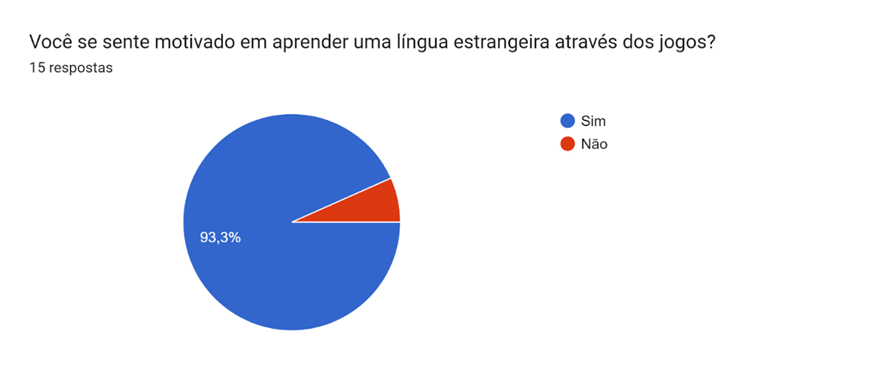

In both scenarios, graphics above, players were more motivated to learn a new language through video games (80%) or (93.3%). It is possible to say that more than half of the respondents were more motivated.

The post-pandemic respondents justified their answers as to why they think it can be more motivating to learn a new language through video games as follows:

- “Acho complicado, aprender apenas algumas palavras :D”

- “existem muitos jogos que estão somente na lingua inglesa, isso faz com que eu empenhe mais em aprender o idioma para não haver a necessidade de um tradutor”

- “caso seja um jogo estilo arcade que não demande muito tempo, eu jogaria”

- ”Eu não jogo muitos jogos com histórias, por não ser o meu gênero preferido, então acredito que eu aprendo pouco inglês com jogos. Mas sim, me sinto motivada”

- ”O jogo até valoriza a cultura do idioma usado pela relevância dele ter sido escolhido como o principal, então a pessoa vincula a história do jogo com o idioma e aí fica MT mais atraente. Alem de gerar um propósito a mais pra aprender”

- ”Aprender um novo idioma para não depender tanto de traduções ou legendas”

- ”Para o pessoal do mundo geekie, se torna mais atrativo, pelo fato de ser uma comunidade com gostos parecidos. Também, além de ser um meio de entretenimento torna-se também um meio de aprendizagem.”

- ”Por conta de ser mais interativo”

- ”Me sinto motivado a jogar com pessoas de outros países”

- ”Exatamente pelo fato de ser mais leve o aprendizado , é como um nativo aprende , natural e gradativo!!”

- ”É mais divertido aprender outro idioma jogando, do que somente aulas.”

- ”Como eu disse, aprendi muito inglês com os jogos, apesar que atualmente eu quase não jogo em inglês… Existem alguns jogos como Stardew Valley que eu faço questão de jogar em inglês, assim acabo aprimorando meu conhecimento”

- ”Acho que é uma forma mais leve e interessante de aprender”

- ”ja fiz curso de espanhol, por conta de um jogo da hello kitty”

- ”Por mais que aprendemos muito por meio dos jogos, não é 100%.”

Just like in the answers above, they claimed that it can be fun to interact with the game; in one of the answers, it is said that they even want to communicate with people from other countries by playing video games.

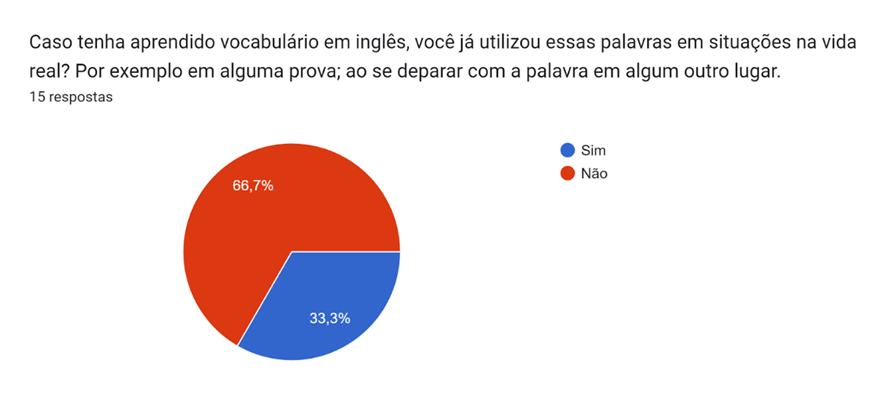

Considering the new vocabulary learned in English, presented on pages 18 and 19, most of the post-pandemic respondents claimed that they didn’t use the words they learned in real-life situations; however, those that claimed that they used the vocabulary learned in League of Legends, 3 out of 15 respondents, said:

- Dentro da comunidade do próprio jogo

- Shorts, crush, acho que existem muitas palavras que utilizamos

- já xinguei alguém no modo liga das lendas

Since the pandemic research was done differently, the question of how they used the words in real-life situations was not included, but we can see a different result when asked about the use of the words in graphic 16 below:

After going through the data so far, the first thing we can say is that the majority of the players from pandemic and post-pandemic times were female players aged 16 to 34 years old, implying that we have a large number of players who are still in school or are about to graduate and for whom English is very important.

Almost all of them agreed that they had already learned a range of vocabulary through the game League of Legends (2009) and games in general, which is alarming data. The words reported as learned vocabulary are shown in table 2 below:

| PANDEMIC | POST-PANDEMIC |

| Várias palavras | ward, fist blood, pentakill, lane, jungle, mid, bot, top |

| Sou fluente em Inglês, mas reconheço que os games foram de grande ajuda durante meu aprendizado desde a infância. | league of legends, wakd, lane, |

| feedar, call, floodar, nerfar | ward |

| Engage, Tank, Shield etc. | bush – arbusto/ wardar – vigiar |

| Meele, ranger, afk, agrar, ks, gankar, summoner entre outras… | Bush, Ward, leash, recall, cooldown |

| No momento lembro somente de Guinea Pig, mas no mais, a maior parte do meu vocabulário de inglês. | wave, backdoor, snare, poke, stun e não lembro o resto |

| Fatality, finish him, ready, go, nice, perfect… | where you are from? how old are you? Hi! I’m fine, and you? |

| w (dub) | Ward, summoner, spell |

| Quiver, bow, fatigue, cooldown, respaw, parry, dexterity, strength, inventory, etc | Farm, Bait, Cait |

| Character, level, power up, shield, | Shield bow , cleanse , heal , ignite… |

| Try hard, worth, spree, “death is like the wind, always by my side”, “Kill steal” ou “kill secured” | Ward, feedar |

| Level, attack, score | Não especificamente em inglês, mas uso muito “tankar” |

| Palavras utilizadas em fps em geral: CT, TR, eco | Ward |

| Easy, Multiplayer,single,language,demo,player e etc. | givar, feed entre outros kkkk |

| Todas as palavras possíveis | feed, kill spree, dive entre outras q n lembro agr kkk |

| win, loss, up, down, mid, são bastantes mas não consigo lembrar kkk | |

| Jinx, ward, ban, sprouts, hazelnut, harvest, lucky, artisan, attempting….(não lembro mais) | |

| Em geral o vocabulário para conversação no jogo | |

| Comandos básicos de ações, ou instruções do personagem “run, jump, punch, save, exit…” e também frases | |

| skill, poison, feed, rush, slow, snare, standart, etc | |

| Noob, quit, rage, rox, afk, brb | |

| nerd, buff, feed, parry, team figth, bomb site, counter entre outros | |

| afk |

With those responses, the majority of them claimed that they had already used the vocabulary learned in the games in real-life situations. A good example of the use of English expressions in the community and in real-life situations is the World League of Legends Games, which take place every year, and in which, despite the fact that the narrators and the audience are both Portuguese speakers, they still use English terms and are able to communicate.

The game analyzed is World 2022: LOUD x FNATICS, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elUYbsBXTZY. It was reported that the following vocabulary was used in 10 minutes of the stream as it is shown in table 3:

| 0:05 | “ meta” |

| 0:33 | “Pickados” |

| 0:42 | “Brokens” |

| 0:52 | “Pick” |

| 0:59 | “First pick” |

| 1:42 | “Top laner” |

| 1:50 | “ranged” |

| 1:55 | “Lane” |

| 2:25 | “Mid Jungle” |

| 2:28 | “Melee” |

| 2:37 | “Matchup” |

| 2:39 | “Mid lane” |

| 3:23 | “ban” |

| 3:27 | “Bot lane” |

| 4:12 | “jungle” |

| 4:18 | “stunar” |

| 4:36 | “Setup” |

| 4:38 | “ultar” |

| 5:07 | “Draft” |

| 5:30 | “cooldown” |

| 6:13 | “solo lane” |

| 6:21 | “stun” |

| 7:04 | “bait” |

| 7:07 | ”Ward’ |

| 8:20 | “Early game” |

| 8:58 | “CS” |

| 9:19 | “last pick” |

| 9:41 | “Flash” |

| 9:52 | “First blood” |

As we could see above, in only 10 minutes, 29 expressions in English were used inside the game community.

All in all, we saw in the analysis that both surveys showed a large number of respondents who agreed that while playing, it is very intuitive and can be motivating to learn English through video games. When asked why they are more motivated to learn English, the majority of them responded that because they are immersed in the narrative and path of the game, they can connect more and the process of acquisition is almost non-noticeable.

The new vocabulary the respondents said that they had learned by playing League of Legends can be easily incorporated in their real-life situations, such as testing or even communicating with others in English. As it was reported in the survey, one of the players claimed that “Me sinto motivado a jogar com pessoas de outros países”, and another player said: “ja fiz curso de espanhol, por conta de um jogo da hello kitty”, and many other responses like these were given.

In line with Osma-Ruiz et. al (2015), Moran (2015), Shahriarpour et. al (2014), and Gee (2009), I assume that when dealing with video games, we are not only dealing with pleasure time but also a very important way of learning English and the social context of it.

Conclusion

We conclude that this study has brought some relevant responses to the research question: How was the video game ‘League of Legends’ (2009) an effective virtual tool for the learning of English language vocabulary during the (post)pandemic? Therefore, we recognize that video games are remarkable educational tools which need to be more explored in the context of school and learning because, as this paper showed, They are very rich in terms of narratives, the use of English among the community, and the immersion that video games can provide to the gamers.

Thus, playing video games is not only a moment of pleasure or a hobby; a lot of people are taking it and developing other skills with or though it, and we need to take this and use it as an advantage in our English classes, not seeing it as an enemy but as a pedagogical tool to make students aware that English is very important to their lives.

Finally, I hope this research has brought some contributions to the Applied Linguistics area of English language teaching and learning and teacher education.

References

ALMEIDA, M.S. Video games: conceitos gerais, números e processo. Palestra on-line. Grupo de Estudos Technology in ELT, Unespar, Campus de Apucarana, 13 de julho de 2022.

BOGDAN, C. R.; BIKLEN, K. S. Investigação qualitativa em educação: uma introdução à teoria e aos métodos. Porto: Porto Editora, 1994. Coleção Ciências da Educação, 1991.

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília, 2018.

DEHGANZADEH, H.; DEHGANZADEH, H. Investigating effects of digital gamification-based language learning: a systematic review. Two Quarterly Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning University of Tabriz, v. 12, n. 25, p. 53-93, 2020.

GEE, J. P. Bons video games e boa aprendizagem. Perspectiva, v. 27, n. 1, p. 167-178, 2009.

JENKINS, H. Convergence culture. Where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

MORAN, J. Educação híbrida: um conceito-chave para a educação, hoje. Ensino híbrido: personalização e tecnologia na educação. Porto Alegre: Penso, p. 27-45, 2015.

OSMA-RUIZ, V. J. et al. Learning English is fun! Increasing motivation through video games. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation. 2015.

SALLES, F. Jogos mais jogados do mundo: 10 games populares em todo o planeta. Zoom. Available at: < https://www.zoom.com.br/console-de-video-game/deumzoom/jogo-maisjogado-do-mundo > Accessed in: May 2021.

SHAHRIARPOUR, N. et al. On the effect of playing digital games on Iranian intermediate EFL learners’ motivation toward learning English vocabularies. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, v. 98, p. 1738- 1743, 2014.

World 2022: LOUD x FNATICS. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elUYbsBXTZY. Access on: Dec. 14th, 2022.

Images were taken from World 2022: LOUD x FNATICS. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elUYbsBXTZY. Access on: Dec. 14th, 2022,

*Sávio Sayuki Satake (Acadêmico de Letras Inglês na Universidade Estadual do Paraná, Unespar, campus de Apucarana). Raquel Silvano Almeida (Orientadora da pesquisa desenvolvida no trabalho de conclusão de curso de Letras Inglês, Universidade Estadual do Paraná, Unespar, campus de Apucarana).

[1] It is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elUYbsBXTZY.

[1] Os jovens têm se engajado cada vez mais como protagonistas da cultura digital, envolvendo-se diretamente em novas formas de interação multimidiática e multimodal e de atuação social em rede, que se realizam de modo cada vez mais ágil. (BRASIL, 2018, p. 61)

[1] Competência 5: Utilizar novas tecnologias, com novas linguagens e modos de interação, para pesquisar, selecionar, compartilhar, posicionar-se e produzir sentidos em práticas de letramento na língua inglesa, de forma ética, crítica e responsável. (BRASIL, p. 246)

[1] Competência 2: Comunicar-se na língua inglesa, por meio do uso variado de linguagens em mídias impressas ou digitais, reconhecendo-a como ferramenta de acesso ao conhecimento, de ampliação das perspectivas e de possibilidades para a compreensão dos valores e interesses de outras culturas e para o exercício do protagonismo social. (BRASIL, p.246)

[1] A aprendizagem é mais significativa quando motivamos os alunos intimamente, quando eles acham sentido nas atividades que propomos, quando consultamos suas motivações profundas, quando se engajam em projetos criativos e socialmente relevantes. (MORAN, 2015 p. 5)

[1] “As pesquisas’ recentes sugerem que as pessoas apenas sabem o que as palavras significam e aprendem novas palavras quando conseguem ligá-las aos tipos de experiências a que elas se referem – ou seja, aos tipos de ações, imagens ou diálogos aos quais aquelas palavras se relacionam (BARSALOU, 1999; GLENBERG, 1997 apud GEE, 2009, p. 6).